By Alison McCaffree, Redistricting Issue Chair

For the 2024 election, new legislative map boundaries will switch half a million people to different districts. On Friday, March 15th, Federal District Court Judge Lasnik handed down the final order for the Soto Palmer v Hobbs lawsuit that declared a Yakima Valley district (LD 15) discriminatory to Latino voters. The order creates a new District 14 with the intent of giving better opportunity for Latino voters to elect a candidate of their choice on an equal basis with other voters. The court’s map also adjusts boundaries in 12 other districts. The unnecessary churn and uncertainty for voters caused by having to make changes at this late date demonstrates why LWVWA supports redistricting reform. A new kind of commission putting people first would minimize partisan influences and emphasize a consensus around what’s best for all communities.

To learn more, please join the Redistricting Reform Task Force for one of two briefings on the Washington State’s new legislative maps. How did we get here? Where do we go next? Register for the virtual discussions taking place on Wednesday, April 10th at 6:30pm and Saturday April 13th at 10:30am.

Where voting district lines are drawn affects every voter’s opportunity to elect representatives who best reflect their thinking. This line-drawing process, known as redistricting, is fundamental to establishing individual voting power, your voting power. Our Washington State maps were redrawn in 2021 to account for population changes following the census. But now, in March 2024, Washington has once again redrawn legislative district lines.

The Swirl.

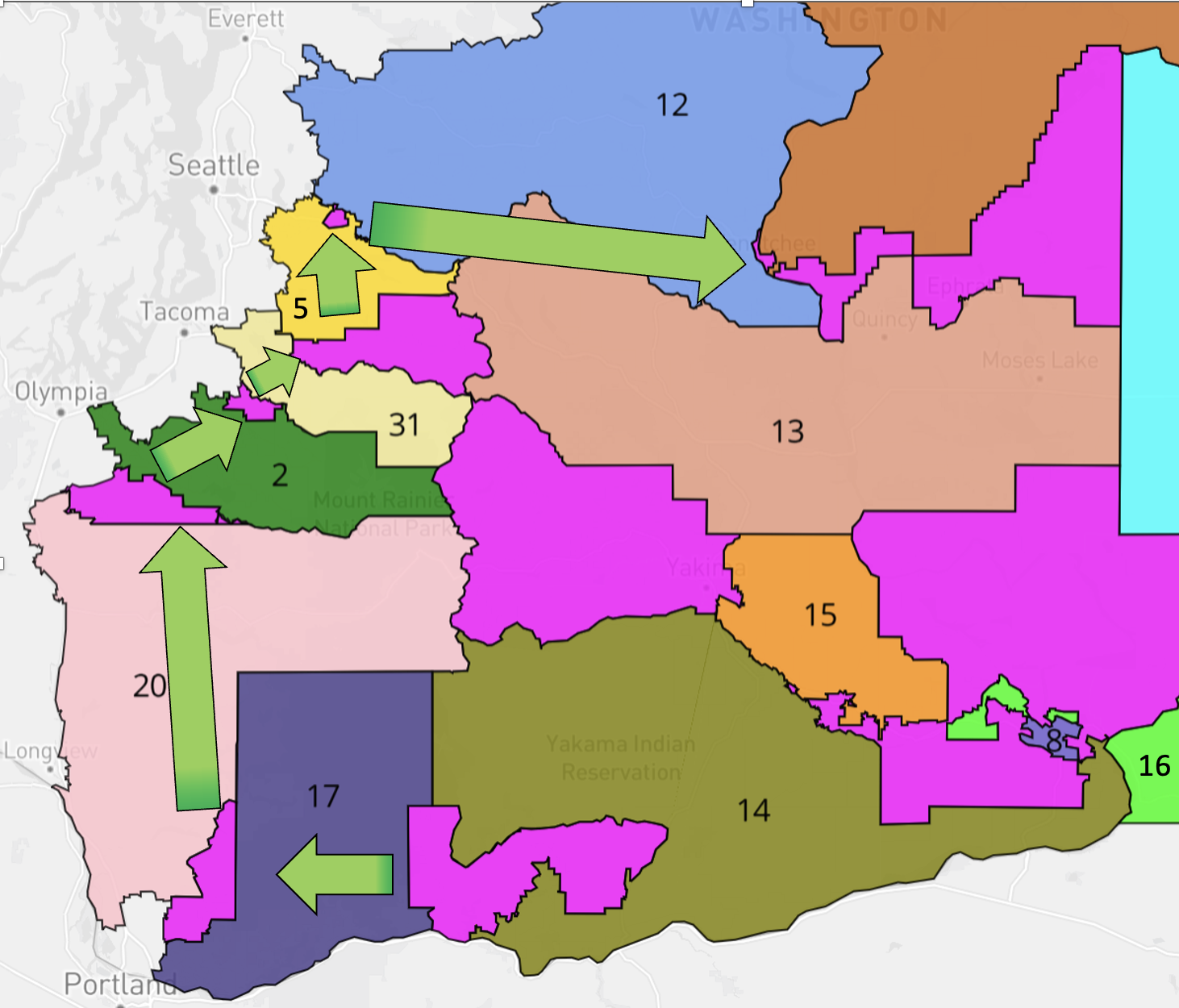

The new legislative map changes thirteen legislative districts: 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 31—with the most significant changes to LD 14 and LD 15. An analysis by The League of Women Voters of Washington’s Redistricting Reform Task Force shows that over 502,000 voters are affected by the changes (See the pink areas in the map below). The new LD14 connects the Latino communities in East Yakima, Yakima Valley and East Pasco and combines it with the Yakama Nation’s main reservation and its fishing villages. According to the court, in this district Latino voters have a better opportunity of electing the candidates of their choice. Creating the new LD14 caused a ripple effect, as the changes swirled through Western Washington districts (note green arrows) to balance population numbers. The Office of the Secretary of State has confirmed that these lines will displace 5 sitting legislators. On March 22nd, the appellate court denied an emergency stay which means the new map will remain in place for the 2024 elections. An appeal process will continue during the summer.

The Swirl: Pink areas highlight the population shift incorporated into the new legislative districts (approx. 502,000 people). Smaller pink areas starting in SW LD14 and moving along the arrows to Wenatchee represent approximately 15,600 people shifted from one district to the next.

The challenge to the map drawn by the 2021 Redistricting Commission was based on a violation of Section 2 of the federal Voting Rights Act. According to Yurij Rudensky of the Brennen Center, Judge Lasnik’s order applied well established legal principles reaffirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 2022 Alabama redistricting case. The court order concluded that 1) the desires of the Yakama Nation were granted, 2) district changes are reasonable given the redistricting process and 3) partisan interests play no part in the new legislative map development and only necessary changes were implemented. Overall, the court’s decision stated that the new map supports the Latino community of interest in Central Washington that has long been underrepresented. The test of the map will be in November when we will see if voters have the chance to elect people who truly represent them.

The Solution.

LWVWA believes the uncertainty and churn caused by this lawsuit illustrates the need to change our state’s redistricting process. People may or may not like the outcome of a lawsuit. Regardless of the ongoing debate, the League believes that this disruption is not good governance. A better process would likely have created a more representative map in the first place and avoided this new change of districts for so many voters.

The Washington State Redistricting Commission, as currently structured, is often described as independent. It is not. Commissioners are put in place by the two major political parties, with work facilitated by a non-voting chair. Court records show that in the 2021 process, Washington State legislators and their staff members were in regular contact with the redistricting commissioners, essentially lobbying for partisan interests. Additionally, court records show there was no public view into their final deliberations. These records report commissioners worked in partisan pairs, finally voting on maps that neither they nor the public had time to study or evaluate. Many LWVWA members directly experienced this exclusion. Ultimately, Commissioners were fined for violations of the Public Meetings Act and faced several lawsuits, including the Soto Palmer action that resulted in the new map.

The League of Women Voters’ national position supports a new type of redistricting commission with expanded representation beyond the current two-party structure. The Redistricting Reform Task Force is calling this a People First Commission. All members of this type of commission are ordinary citizens who represent Democratic, Republican, and other points of view but who are not officially affiliated with the political parties. A People First Commission puts people’s interests above partisan tradeoffs. The League believes district line drawing should be accomplished in an open, unbiased manner with citizen participation and access at all levels and steps of the process. Our position supports a prompt review and rule by the courts on any challenge to a redistricting plan and requires adjustments if the standards have not been met.

Good models exist in other states. According to analysis of California’s commission, their People First approach is more transparent and accountable, maximizes opportunities for involvement, and ensures the broadest possible representation. The 2020 California Citizen Redistricting Commission’s final report states that they produced fully vetted maps designed to best serve the people of the state. Recent research from University of Southern California, “Fair Maps in the State of California,” shows that these types of commissions have higher public trust and have resulted in legislatures that are more representative of the people in their state. This Fair Maps report concludes, “The result is a process that empowers communities and reduces the influence of political actors.” The LWVWA supports a People First Commission for Washington.

See lwvwa.org/redistricting for more information on how to get involved.